Generation Hispanic TV - Live

Just Another Costume: Late Chronicles of a Gender Expression “Experiment”

Just Another Costume: Late Chronicles of a Gender Expression “Experiment”

[simple-author-box]

“If you don’t tell me if you’re a boy or a girl I’ll stick this pen up your…”. This sentence pretty much sums up my middle school period: three years characterised by hormonal awakening, body changes, acne, questionable fashion trends and ultra-filtered selfies. The years where kids start that rollercoaster called adolescence, in which they experience the first beams of independence, confusion and increased emotions; where they start to explore their tastes in clothing and music, and divide into a hundred different styles, personalities and subcultures.

The first thing that springs to mind when I think of my early adolescence is a very clear image of myself: large dark t-shirts, a wrecked pair of converse and very short hair. I must admit that 90% of my style choices were influenced by my devotion to The Clash: I had listened to them since I was nine years old, and since ending the primary school chapter – made of Rapunzel-like hair and uniforms – I decided to follow the fashion rules of 1977’s London punk scene. Dr Martens, skinny jeans, shapeless t-shirts and hoodies, DIY printed clothing, chains, safety pins and hair gel became part of my everyday wardrobe throughout that whole era. My parents weren’t particularly discouraging my punk outfits and my tomboy-ish figure (as long as it made me happy), not even when the people around them were asking “oh, is that your son?”: I’ve lost the count of all the times I’ve heard that question, to which my parents would reply with a hopeless eye roll and a slightly irritated “she’s our daughter, she’s not a boy”. When I was 11, I wouldn’t get upset by people referring to me as a boy, because back then I didn’t want to act like a girl at all.

The “pick me girl” phenomenon is well-known by now on the internet: just for example, youtube is full of video essays explaining what it is excellently and in depth. For anyone who doesn’t know what a pick me girl is, it’s a behaviour that can be summarised with the phrase “I’m not like the other girls”: it’s a very toxic mindset, rooted in internalised misogyny and has as only aim to win male attention, to appear (desperately) as “one of the boys”; it can be expressed in a variety of ways, from a rejection of whatever is considered to be “feminine” and “popular”, to very strong critics and denigration towards other women. In short, it’s a woman who hurts other women in order to become the men’s favourite. Sadly enough, throughout the majority of my teenage years, I was a pick me girl: even though most of my friends and acquaintances were female, I used to think they were incredibly shallow just for wearing make-up and being obsessed with their appearance, romance and boys. I used to have respect for a very few of them, but every other girl was like an enemy to me, a threat to my own existence. After all, I was obsessed with boys too and I was craving them with all my silly attempts at being “not like other girls”. Also, whoever has been on the internet roughly from 2011 to 2016, would certainly remember that kind of posts that some adolescents in particular where sharing: memes that were constantly comparing the “other girl” with the “edgy girl”, only to show how worthless the first one was and how cool was the latter. I shiver in discomfort just by reminiscing it, as I was one of those sharing that stuff too. It was everywhere. We had no choice but to believe it was relatable.

So with that said, the biggest curse that could ever happen to me was to be born a girl – and being expected to act as one. My clothes and music taste (even though I genuinely enjoyed them) were a way to shake off my shoulders the hyper-femininity of most of my childhood, which – as usually happens – was more imposed than chosen: it’s a common belief that girls naturally tend towards activities that involve pretty clothes, make-up, taking care of babies and generally caring about their physical appearance. The 11-years-old me thought that rock music and being pretty were two incomparable things; that I couldn’t listen to Joe Strummer sing about Nicaraguan sandinistas while spreading colourful eyeshadow on my lids.

It’s very easy to notice how adults – particularly women – usually put a huge emphasis on little girls’ aesthetics, as if the outside is more important than the inside. Some people do this unconsciously, instinctively pouring a waterfall of compliments on every small female human they encounter because we’re taught this is the default; but this eventually has its consequences. As Emer O’Toole puts it in her book “Girls Will Be Girls: Dressing Up, Playing Parts and Daring to Act Differently”, compliments on physical appearance become the standard interaction between adults and little girls from very early on, as well as beauty rituals between the latter and women in the family: this approach – if prolonged throughout time – can lead to strong insecurities that will grow throughout teenagehood; also, girls will learn that their own worth is associated with their appearance, and that they’re deserving of love only if they’re pretty. Even if I couldn’t articulate my thoughts in such an immaculate manner, my early teenage self thought that this behavioural system was stupid and oppressive, and that my mission was to prove that I was deserving of love and attention because I was smart and alternative, not because I acted like a lady and followed socially-approved beauty standards. I was willing to take the risk to become ugly, if this helped my brain to shine through. And in our society, if you don’t care (or, in my case, refuse to care) about all the things traditionally attributed to femininity, you’re automatically a boy.

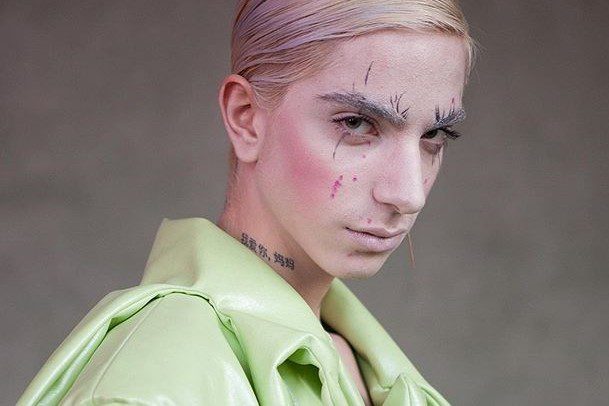

Around the age of 12 I became a huge fan of Placebo: the British band formed in the 90s famous for their bittersweet songs, their connection with the LGBTQ+ community and their gender-bending style. Even though their aesthetics have evolved considerably through the years, I guess the first thing that comes on everyone’s minds when thinking about them is how they presented themselves throughout the last decade of the 20th century, when their career arose: singer Brian Molko in particular made androgyny his distinguishing trait, with make-up, dresses and a dark bob haircut. As it always happens, I fell in love both with their music and their image, and thanks to Placebo I partially turned from a scruffy punk into something less chaotic; also, my everything-but-feminine appearance had one more reason to exist, and this had to do with the (very funny) idea to confuse people even more than they already were.

The turning point came when I read an interview to Brian Molko in which he said that the band wanted to use cross-dressing as a political act, to react to the homophobia they’ve witnessed in the music scene, adding that “I wanted anybody who was slightly homophobic in the audience to look at me and go, ‘ooh, she’s hot. I’d like to fuck her’, before realising that ‘her’ name was Brian, and then have to ask themselves a few questions about […] the fluidity of sexuality itself”; then the rest is history. The idea of challenging people’s stereotypes regarding gender expression felt pretty exciting to me: I could take the piss of their prejudices on how I was supposed to look like as a teenage girl.

With the wisdom that comes with age, when I look back at my revolutionary attempts at confusing people about my gender, I can’t help but see some kind of scientific spirit in it. I was doing all these kind of experiments to disguise myself as much as I could, and every human interaction was an occasion to collect new results. I became and actor that before going on stage in the outside world had to wear her costumes, play a part in front of her audience and observe their reaction. It eventually took me years to realise that what I was doing wasn’t just a tantrum dictated by teenage angst: it paved the way to a long path of self-discovery that made me who I am now. And to do that, my early teenage self went through quite some incomprehension and bullying. But first things first.

With Brian Molko’s words carved into my mind, I started my mission. First of all, I had to focus on the outside: my hair became shorter, my unibrow remained untouched and my face covered in acne never met a layer of foundation. My body, which was just starting to get out of childhood into puberty – with its undefined and green curves -, was enveloped in neutral, shapeless clothes. I had accomplished a quite satisfying level of androgyny, but there’s one little detail I can’t help but smirk when thinking about it: I was shaving my legs with obsessive precision – the most feminine thing I could ever do. As I said earlier borrowing Emer O’Toole’s words, little girls create bonds with female relatives mainly through beauty practices: in my case, my mum and I strengthened our relationship on the long way to womanhood when she taught me how to use a razor. If on one side this allowed us to create a little space of intimacy where my mum would gradually teach me how to become a woman (whether I liked it or not), on the other it marked the start of that body-shaming process that everyone had to deal with at some point in their lives – and with a beautician somewhere in the family, it was particularly stressing. So I was a girl who didn’t look exactly like a girl but who had perfectly smooth legs and armpits. I can go on for hours about body hair and how much shame revolves around something that is so natural – a process that usually starts in adolescence and creates so much anxiety and paranoia -, but this is not the main point of this article. My teenage self has a research to do.

As I expected, the funniest part was seeing people’s reactions. The elderly were the ones that gave me more satisfactions – maybe because they usually have more prejudices on gender expression. I would always have a laugh when an old lady would mistake me for a boy, or tell my mum “oh, you’ve got such a well-mannered and good-looking son!”. And the best thing was replying with a simple “excuse me, my name is Agnese”, as Brian Molko taught me to do. At that point, a small flame of panic would ignite on their faces, their eyes frantically looking at me in a desperate attempt to give a rational reason to that information. But why did this happen?

Psychologist Jean Piaget theorised the concept of schema, which can be described as a basic mental structure that allows us to collect and organise actions, convictions and ideas. Schemas are useful because they simplify the way we understand the world and allow us to do lots of things without difficulties; on the other hand, this simplification can be too much sometimes, making it hard for us to go beyond stereotypes. Schemas have a big part in our understandings of gender: throughout our lives, we’ve built schemas on masculinity and femininity, made of certain characteristics; so, whenever we see a person displaying a coherent amount of those characteristics, we identify them either as a man or as a woman – nothing in between. Most people, looking superficially at my general appearance, assumed I was a boy because their schema told them so; but a deeper dive would prove the contrary. Only recently I understood that this was one of the main reasons (if not the sole reason) behind this confusion: at first sight, those schemas wouldn’t accept that a boy could be named Agnese, and that a girl couldn’t look feminine. Anyway, these schemas aren’t fixed and with some effort they can be updated and deconstructed. Another psychologist called Sandra Bem has defined schemas as “gender lenses”, through which we see people in terms of gender stereotypes: we can always look at these lenses – instead of looking through them – to understand and change the way we consider the people around us.

My observations got even more interesting at school, a place that during adolescence is mostly hostile and terrifying: in those years, I learned how insensitive teenagers could be, and sometimes violent too. Students staring insistently at me and whispering imaginative assumptions about my gender behind my back, or just laughing at how ambiguous I was, became part of my everyday routine. Sometimes, while minding my business, I would have sent my way a poor soul who was in charge of the unfortunate mission to get the information on whether I was a boy or a girl, while his mates were giggling at us at a distance. Thinking back to it now, I don’t have any idea on how I survived all of this: the amount of mortification and violation of my private space I had to deal with everyday in those three years was unbearable. But I didn’t want to give up: that would’ve meant that they were winning, but I sincerely enjoyed my appearance and they had to simply accept it.

The neighbourhood I was born, grew up and still live in is of a mixed middle class-working class background: it’s an area almost entirely populated by traditional, catholic heterosexual families that raised their kids according to the gender binary norms. Unfortunately I’d say, most of these children never questioned these precepts, continuing the customs of their parents, grandparents and whoever came before them. As a consequence, when confronted with people that don’t adhere to those rules, their little brains (or schemas) reject them: not as in ignoring them, but more as in nagging them. And so we go back to the line that opens this article (if you don’t remember it, I warmly suggest you to go up again and read it, it’ll be useful soon).

I still remember as it was yesterday when I heard that phrase for the first (and luckily last) time – a line that represented the climax of my experiment. I was at school, and as it always happened when a teacher wouldn’t turn up, my classmates and I would be divided between the other classrooms. My terror every time was to end up in a classroom with older kids – and, even worse, during the lunch break -, cos it always meant one thing: bullying. Unfortunately, that time was the case: I sat uncomfortably in a corner of the room, with all these youngsters looking at me as if I was a freak, and waiting impatiently for the bell to ring so they could find out to which category that creature belonged; and when the lunch break came, it felt like when the bull is set free into the arena at the Corrida. I had all these insistent eyes around me, getting more evil with every gaze, murmuring and calling me names: their schemas weren’t accepting the existence of an androgynous being and this was pissing them off in an unimaginable way. The computers inside their brains were exploding.

Then this guy came up to me. He was holding a pen in his hand and had flames in his eyes. He put his fuming face right at a few centimetres from mine and hissed that sentence, that hurt like a sword in my stomach. “If you don’t tell me if you’re a boy or a girl I’ll stick this pen up your ass”. I stopped breathing, completely static and overwhelmed with fear. These moments are a matter of seconds but seem to last for ages, and you never know what to do ‘cause you fear that every thing would lead to an even worse nightmare.

I’m still not sure why these situations escalate in this way, but it proves an undeniable link between ignorance, intolerance and violence. I don’t know if the concept of schema is enough to explain it or there’s something else that I still haven’t found out. What I know is that my experiences have led me to the conclusion that our looks are political, and that they’re not much different from a performance: the more you experiment with the way you present yourself, the more you question a strictly binary system that’s oppressive, and the more you prove that it’s all a farce.

Now I don’t look like a boy anymore (even though some of my friends affirm that I’ve kept a good amount of androgyny anyway): I overcame my pick me girl phase, I’ve let my hair grow, I occasionally wear dresses and heels and have lots of fun with make-up. But even though I mostly present myself in a way that’s traditionally associated with the gender I’ve been assigned at birth, I’ve got my exceptions – that are funnily considered “masculine”. I don’t think my looks right now are an expression of who I’ve always been but wanted to hide because of a teenage rebellion: I like to think that every look I’ve adopted was something that was true to a specific phase of my life. This one’s just another performance, just another costume. I don’t know if I’ll stick to this look for the rest of my life or I’ll change – shocking and upsetting people again -, but I don’t think I even care. I’m only hoping for a time when people will stop sticking to the gender binary rules believing they’re somehow “natural” and “necessary” and just let everyone be free of be whoever they want to be, as there’s no such thing as the categories of “man” and “woman” that are dramatically different and incomparable in every single part. I hope people will understand that it’s more what we have in common than what divides us, and that we’re first of all human beings each with their own personality, tastes and needs.